Source: Zero Hedge

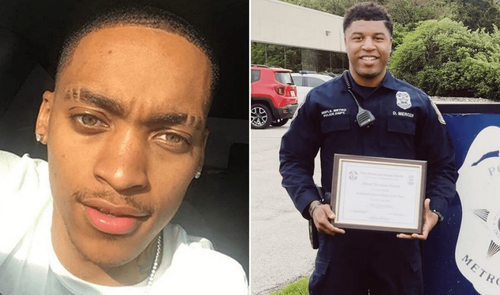

There is an interesting lawsuit out of Indiana where Indianapolis Metro Police Department Officer De’Joure Mercer is suing the National Football League (NFL) for defamation after the NFL claimed that his shooting of an African American man was due to “systemic racism.” (Officer Mercer is also African American).

The suspect, Dreasjon Reed, reportedly fired repeatedly at Mercer before he killed him — a shooting found to be justified by the a review board.

A special prosecutor also announced that a grand jury rejected any charges against Mercer.

The complaint below details how Reed stole a handgun from a pawn shop in Texas and livestreamed himself committing a “drive-by” shooting in which he fired the stolen handgun blindly into buildings as he drove past.

He also livestreamed his encounter with police on May 6, 2020 with the gun visible.

In the video, Reed talks about not “going back to jail,” which could be a reference to the three outstanding warrants for his arrest. Reed had been driving recklessly and hit a couple of vehicles. The video captures when, around 6 pm, Metro Police Deputy Chief Kendale Adams had ordered a stop to the high speech chase that ensued after Reed refused to pull over. Adams was concerned about the safety of the public in any high speed chase but Mercer continued to watch Reed at a distance. Reed, as shown in the video, then pulls into a local business and attempts to flee on foot. Mercer chased him and eventually shot him with a taser. Reed however pulled his handgun from his waistband and fired two rounds at Mercer. Mercer then returned fire and killed him.

The use of force in such a circumstance is justified under Indiana Code 35-41-3-3(b):

A law enforcement officer is justified in using reasonable force if the officer reasonably believes that the force is necessary to effect a lawful arrest. However, an officer is justified in using deadly force only if the officer:

(1) has probable cause to believe that that deadly force is necessary:

(A) to prevent the commission of a forcible felony; or

(B) to effect an arrest of a person who the officer has probable cause to believe poses a threat of serious bodily injury to the officer or a third person; and

(2) has given a warning, if feasible, to the person against whom the deadly force is to be used.

Indeed, a private citizen would be protected in the use of such force under Indiana Code §35-41-3-2.

That was the conclusion of a grand jury and a detective and a police review board.

It was not apparently the conclusion of thousands of protesters who took to the streets after the shooting or ultimately the NFL. On Sept. 11, 2020, the NFL published a video a part of its “Say Their Stories” campaign featuring Reed. During the video, the NFL also mentioned the NFL would honor the “victims of social injustice” by wearing their names on their hats and helmets and tell their stories including Reed.

What is striking is that the NFL knew all of this. Jim Irsay, the owner of the NFL’s Indianapolis Colts, is quoted in the complaint as saying that the NFLE’s Tweet and Facebook Publication contained “misinformation.” Likewise, various law enforcement officials objected to the inclusion of Reed as one of those “honored” as a victim of systemic racism.

The NFL under Commissioner Roger Goodell ignored the objections or the harm to Officer Mercer. On Dec. 16, 2020, the NFL tweeted a caption and picture of Reed, noting Reed was “one of the many individuals being honored by players and coaches this season through the NFL’s helmet decal program.” A Facebook post with the same photo and caption was also posted to the NFL’s page on the same day.

Say His Name: Dreasjon Reed

Dreasjon is one of the many individuals being honored by players and coaches this season through the NFL’s helmet decal program.#SayTheirStories: https://t.co/vwi75WmNxr pic.twitter.com/wWaasw6LBp— NFL (@NFL) December 16, 2020

As a result of this ill-informed campaign, Mercer received death threats, including a “wanted” poster with Mercer’s image on it. His picture was circulated online.

We have previously discussed the NFL and other corporate campaigns in this area.

However, this is now a defamation action which could present significant challenges based on the elements for the tort.

The complaint alleges per se defamation. Those per se categories commonly include (1) “imputation of certain crimes” to the plaintiff; (2) “imputation . . . of a loathsome disease” to the plaintiff; (3) “imputation . . . of unchastity to a woman;” or (4) defamation “affecting the plaintiff in his business, trade, profession, or office.” This would seem to suggest not just a criminal act (in an unjustified shooting) but an attack on Mercer’s profession or trade as a police officer.

The NFL could try to impose a higher burden of proof on Mercer as a public official or public figure. The standard for defamation for public figures and officials in the United States is the product of a decision decades ago in New York Times v. Sullivan. The Supreme Court ruled that tort law could not be used to overcome First Amendment protections for free speech or the free press. The Court sought to create “breathing space” for the media by articulating that standard that now applies to both public officials and public figures.

The Supreme Court has held that public figure status applies when someone “thrust[s] himself into the vortex of [the] public issue [and] engage[s] the public’s attention in an attempt to influence its outcome.” A limited-purpose public figure status applies if someone voluntarily “draw[s] attention to himself” or allows himself to become part of a controversy “as a fulcrum to create public discussion.” Wolston v. Reader’s Digest Association, 443 U.S. 157, 168 (1979). At most Mercer would be a limited public figure if he gave interviews or voluntarily sought to publicly defend himself.

If found either a public official or a public figure, Mercer would have to show either actual knowledge of its falsity or a reckless disregard of the truth. Moreover, the NFL is not a journalistic organization and thus cannot claim privilege or special protections.

There are a couple of issues that might arise immediately. One is that the NFL does not mention Mercer even though he was quickly identified on the Internet and widely referenced in the news. One can always litigate such a claim as a per quod case where defamation occurs by reference to extrinsic facts. Moreover, Mercer was already being attacked before the NFL campaign by protesters and critics who viewed the shooting as racist.

The biggest challenge is that this could be viewed as an opinion on a controversial shooting. Many clearly viewed the shooting as an example of systemic racism and the NFL was adopting the same view of the protesters over the case. The case in favor of the Mercer is very strong, indeed unassailable, in my view. However, people, including corporations, are allowed to reach their own conclusions.

Courts have been highly protective over the expression of opinion in the interests of free speech. This issue was addressed in Ollman v. Evans 750 F.2d 970 (D.C. Cir. 1984). In that case, Novak and Evans wrote a scathing piece, including what Ollman stated were clear misrepresentations. The court acknowledges that “the most troublesome statement in the column . . . [is] an anonymous political science professor is quoted as saying: ‘Ollman has no status within the profession but is a pure and simple activist.’” Ollman sued but Judge Kenneth Starr wrote for the D.C. Circuit in finding no basis for defamation. This passage would seem relevant for secondary posters and activists using the article to criticize the family:

The reasonable reader who peruses an Evans and Novak column on the editorial or Op-Ed page is fully aware that the statements found there are not “hard” news like those printed on the front page or elsewhere in the news sections of the newspaper. Readers expect that columnists will make strong statements, sometimes phrased in a polemical manner that would hardly be considered balanced or fair elsewhere in the newspaper. National Rifle Association v. Dayton Newspaper, Inc., supra, 555 F.Supp. at 1309. That proposition is inherent in the very notion of an “Op-Ed page.” Because of obvious space limitations, it is also manifest that columnists or commentators will express themselves in condensed fashion without providing what might be considered the full picture. Columnists are, after all, writing a column, not a full-length scholarly article or a book. This broad understanding of the traditional function of a column like Evans and Novak will therefore predispose the average reader to regard what is found there to be opinion.

A reader of this particular Evans and Novak column would also have been influenced by the column’s express purpose. The columnists laid squarely before the reader their interest in ending what they deemed a “frivolous” debate among politicians over whether Mr. Ollman’s political beliefs should bar him from becoming head of the Department of Government and Politics at the University of Maryland. Instead, the authors plainly intimated in the column’s lead paragraph that they wanted to spark a more appropriate debate within academia over whether Mr. Ollman’s purpose in teaching was to indoctrinate his students. Later in the column, they openly questioned the measure or method of Professor Ollman’s scholarship. Evans and Novak made it clear that they were not purporting to set forth definitive conclusions, but instead meant to ventilate what in their view constituted the central questions raised by Mr. Ollman’s prospective appointment.

The NFL could claim that no one would confuse a public anti-racism campaign with a source of factual discourse as opposed to opinion on such shootings. It is of course an embarrassing defense in light of the obvious premise of the campaign. The NFL was clearly launching the campaign to convey the fact of systemic racism in such police shootings. It would now have to argue that such cases are merely opinion and could be false.

While the NFL should be roundly condemned for the inclusion of the case, this will likely be a challenging defamation case. However, while novel, it is not frivolous. The court will have to address the line between opinion and fact in this context. The question is whether the NFL could be viewed as stating as a fact that this was a racist shooting. It is not enough to simply state “this is just my opinion” if it is followed by what sounds like an asserted fact.

There are countervailing free speech concerns in allowing people (including corporations) to be sued for viewing such shootings in a different light from the police or review boards. For example, what is the difference between this and a columnist writing an article that the shooting was part of a pattern of racism? The NFL did not state any false facts other than its highly (and legitimately) contested conclusion. It did not state that Reed was unarmed or did not fire at Mercer. It simply viewed the shooting as part of the systemic racism in our society.

In my view, the inclusion of the Reed case was not just “misinformation” but reckless and wrong. The NFL knew or should have known that the claim was false. Moreover, the impact on Officer Mercer was obvious as the officer responsible for what the NFL suggested was a racist shooting. It “honored Reed” and by implication condemned Mercer. The only question is whether this is actionable as a matter of torts. The odds favor the NFL but this could prove an interesting and important case exploring the limits of an opinion defense.

Here is the complaint: Mercer-complaint